Chapter 13 - Cost Breakdown and Budget¶

Part 2¶

Estimating resource requirements, project costs and measuring the performance¶

Media coverage of project scandals often focuses on cost overruns rather than missed deadlines. Notorious examples can be found in public sector construction projects (e.g. Berlin Brandenburg Airport, London City Garden Bridge, Saint Helena Airport). Recently, taxpayer-funded construction projects in which the costs vastly exceeded the original budget produced negative headlines. Most of the criticism comes from central and regional government auditing authorities. Private-sector enterprises, on the other hand, tend not to disclose these kinds of management blunders. They fear the loss of image associated with failed projects.

There are two types of costs:

- Variable costs (e.g. electricity, sales commission and shipping costs)

- Fixed costs (e.g. insurance, salaries and rent for office space)

Those overruns also often jeopardise the organisation's other projects and objectives. For example, if the budget for a public-sector road construction project is overrun, there will be a lack of funds for other construction projects. In this case, the other projects will either be delayed or terminated. Organisations face the same problem. If project managers overrun the budget for their project, there will be a shortage of funds for concurrent or planned projects. Escalating project costs can also threaten an organisation's existence if the order is large relative to turnover. Cost overruns - especially in internal projects - are often the reason why organisations fail to meet profitability targets. Most cost types can be quantified in easily recognized amounts. For example, personnel and material costs are quantified in terms of the number of person hours or units of material consumed. This is why most cost budgeting methods deliver information about the anticipated quantities rather than direct cost values. The commercial project team members then use the relevant cost rates to convert quantities into costs.

Cost budgeting methods¶

The use of work breakdown structures in cost budgeting¶

A work breakdown structure is absolutely essential in almost all of the methods used to estimate costs. When you estimate the costs associated with a project you must initially consider the components of the project deliverable. At a minimum you estimate these costs on the basis of a subjective WBS, even though it may still be unsystematic and have very low structural depth. Often, it will not even have been set down in writing.

The systematic use of cost budgeting methods in conjunction with the work breakdown structure is dependent on

- the approval of the WBS by your project management team and departments,

- a precise as possible specification of individual items and work packages,

- identical information for all persons involved in cost estimating and

- acceptance of the WBS as binding.

Cost budgeting based on expert surveys¶

Experts are needed in order to make each cost estimate. Expert-survey methods are structured methods in which experts are surveyed to obtain cost estimates. In the past many attempts have been made to use the Delphi method as a means of project cost estimating (an expert survey with several rounds of questioning). This method was not a major success for several reasons:

- It is very difficult to ensure that surveys remain anonymous in organisations.

- The surveys involve several time-consuming rounds of questioning.

- There is no knowledge transfer between the experts surveyed.

Objectives

The main objective of the estimate meeting is to calculate total project costs as precisely as possible. The estimates relate to the specification of inputs expected to be necessary for the work packages. These estimates are multiplied by cost rates and entered into a computer system to enable project-specific cost management. Systematic surveys of experts help you to achieve a number of secondary objectives:

- To enable work package-specific, structured communication between project team members,

- to bring to light as many undisclosed assumptions and prerequisites relating to the project as possible (e.g. dependencies on other departments, availability of human resources),

- to assure management and the project team that the project plan is actually workable,

- to develop a common basis of work and communication for all working and status meetings.

An estimate meeting therefore fulfils more or less the same function as a project start-up meeting. However, the focus in this case is budgeting and cost estimates.

Participants

There are four roles in the meeting:

- Estimator

- Expert

- Chairman

- Keeper of minutes

Cost estimating with cost ratios and code systems¶

In recent years - particularly in English-speaking countries and Germany - project cost databases have been created as a useful tool for budgeting costs in new projects. They enable organisations to take advantage of valuable experience gained from earlier projects.

On the other hand, simple key cost indicators have been used for quite some time now to work out the financial aspects of a bid or in early project phases. Key cost indicators such as

- CHFs per cubic metre of undeveloped land,

- CHFs or person months per code line or

- CHFs per kilogram of machine

are examples of these. One of the methods used by the plant construction industry to work out the financial aspects of a bid is the "cost per kilo" method which is based on a simple principle and delivers fast results.

Prerequisites for project cost databases

If you want to introduce a project cost database you must ensure that three prerequisites are met:

- Data on costs in projects that have already been implemented should be defined, collected, stored and updated in such a way that they are available and relevant for future projects.

- New projects should be structured in such a way that the elements for which cost data was stored in the database form at least part of the planning process.

- Tools should exist to combine cost data relating to completed projects and the work breakdown structures for new projects to produce a cost budget.

Parametric cost estimates¶

Parametric cost estimates are carried out using cost equations in which the project costs, sub-project costs or the specification of inputs are shown in relation to cost drivers. The following equation was derived from data relating to completed projects in the aircraft development industry on the basis of regression analysis. It is suitable for the early phases of the project, when you have little knowledge about the system to be developed.

Resource planning procedure¶

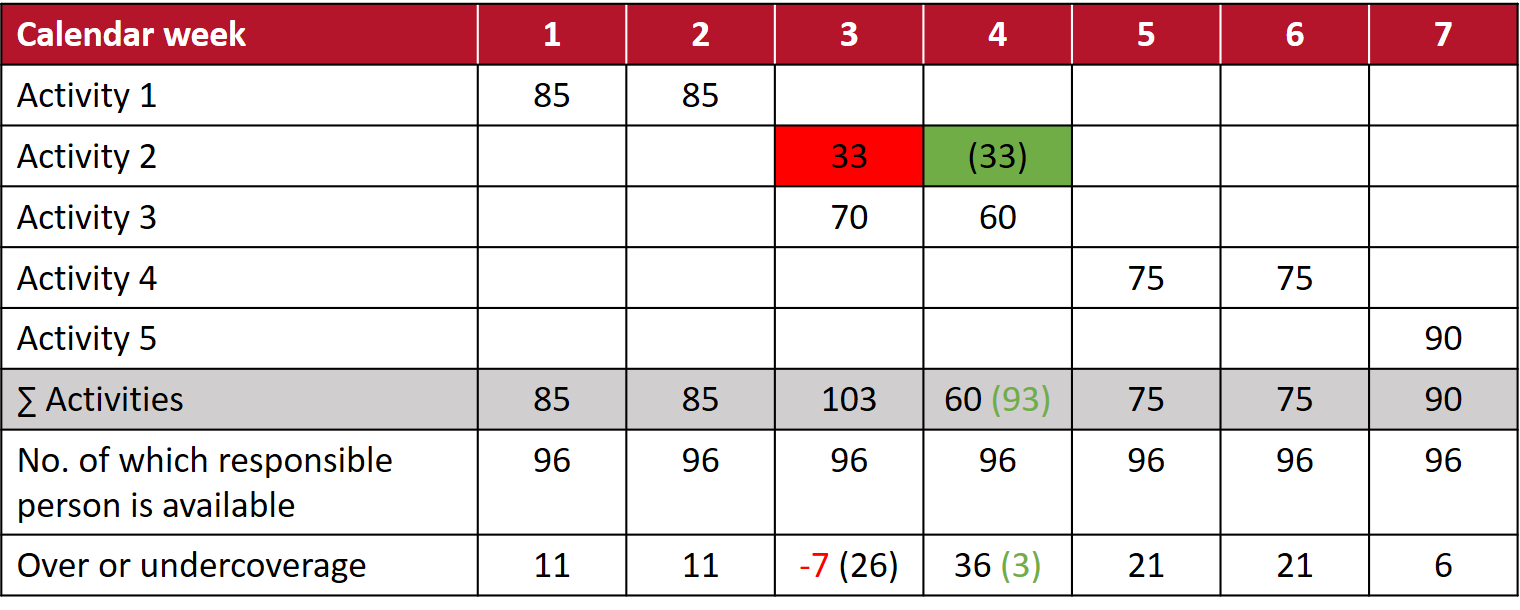

At first glance, network analysis appears to be an enticing option for project-specific resource planning. Resources can be allocated to the various activities or work packages in a network diagram. In this process, the required hours or material units can be evenly distributed along the time axis or allocated on a needs-oriented basis to various workdays or weeks. Since the calendar dates for the start and finish of the various activities and work packages have been calculated, it is possible to distribute the required resources over the calendar axis. But as soon as you need resources for more than one activity at the same time, resource allocation problems arise. To visualise and to solve those problems a resource usage diagram can be useful:

You could postpone an activity, even if the program has scheduled it for an earlier date, if you assume that one of your team members will be assigned to other duties in the planned moment and has time for working on the activity at a later time. There are other ways of reducing capacity peaks. They include, for example, the prolongation, splitting or cancellation of activities.

Performance measurement¶

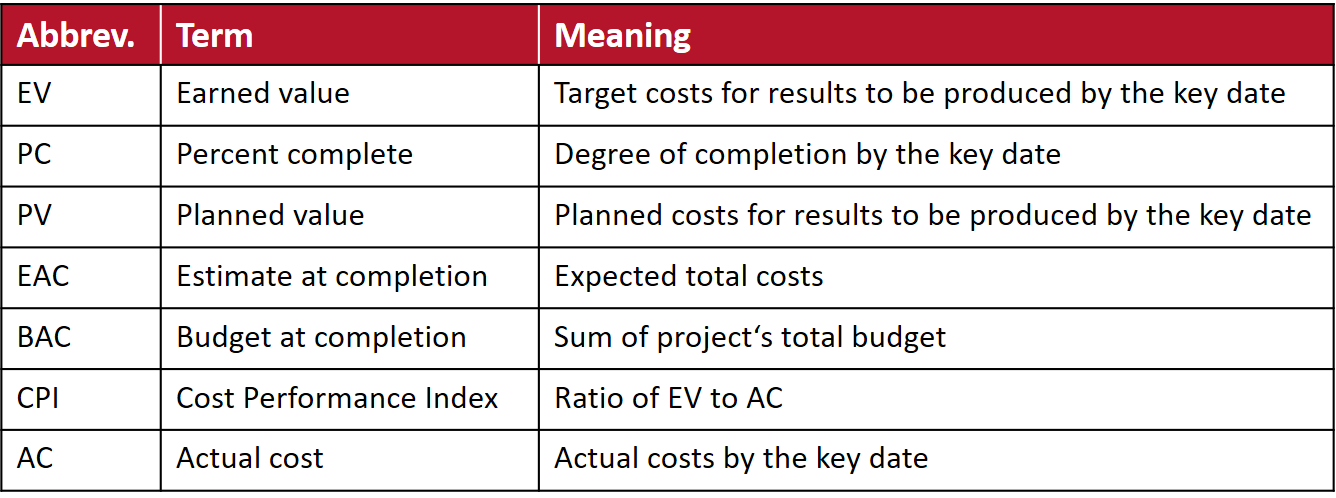

In the process of project-specific cost monitoring, it is initially assumed that progress monitoring will be unproblematic and that the projected costs of work performed (earned value, actual cost to complete, value of work performed and budgeted cost of work performed) will be easy to ascertain. Project cost management does not deliver the necessary information unless data about the project's progress is also available. To calculate the actual performance of the project and the overall progress there are some options available:

-

Calculation of overall earned value

- EV = PC x PV

- EV = ∑EVi for each activity i

(Sum of every individual EV of each activity)

-

Planned-actual comparison and forecast

- EAC = BAC⁄CPI

- EAC = AC + BAC - EV

Problems associated with performance measurement

- Lack of yardsticks

- Time-delayed assessment of the fulfilment of objectives

- Variance analyses with no informative value

How the story ends…¶

Harry Anson, the software specialist, came across these conflicts before, so he suggests creating a process schedule at work package level to provide a good overview of the project. Only the risky work packages would be additionally incorporated at activity level.

Grace Holmes contributes another alternative idea: "How about entering the individual project phases first? We could enter the current phase at activity level because we already have all the details. Then, the next phases can be sub-divided into work packages and the ones that won't be implemented until a distant future date can be treated as sub-projects. If we do that, we can reduce the individual elements in the process schedule and be flexible if we have to incorporate new knowledge. The process schedule will be a kind of phase-oriented rolling forecast that we can update."

Chris Feldmann likes Grace Holmes' suggestion and the rest of the team agrees on it, too.